In this blog post, I will strive to provide a down-to-earth introduction to “exotic” floating-point formats, with a special focus on how they can be leveraged to efficiently train large-scale AI models. By the end of this blog post, you will be aware of both the positive and negative implications regarding the use of these formats as opposed to more traditional ones like float 32, and hence be able to determine which one lends itself best to your use case.

Before we dive into the core of this blog post, you may enjoy an introduction or recap (depending on your prior knowledge) to floating-point formats and the IEEE 754 standard. However, if you are already familiar with such concepts, you may jump directly to Exotic floating-point formats.

Introduction

Let’s face it: most, if not all, of the calculations that are carried out to solve interesting problems involve non-integer numbers. If our whole existence revolved around counting how many apples Alice has left after giving some to her friend Bob, integers (in fact, natural numbers (\(\mathbb{N}\))) would do just fine. However, if we wish to calculate, say, the exact time a solar eclipse will occur at your location, then we can’t do without real numbers (\(\mathbb{R}\)).

Additionally, because pen-and-paper calculations don’t scale very well to real-world problems, people devised smart ways to handle them by means of a computer. However, this poses challenges like how to represent real numbers and how to perform basic operations over them like addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and so on, while also taking care of edge case (for example, division by zero). This blog post is mostly concerned with the first of the two aspects.

There are two possible representations for real numbers1 inside a computer: fixed-point and floating-point. Using a fixed-point representation, we fix once and for all the number of digits to store for the fractional part of a number (that is, the excess over its integer part). While this might sound simplistic, it’s actually good enough for certain purposes. For instance, to represent the fractional part of currency values, you only need two digits (except for cryptocurrencies maybe, but you get my point).

Using a floating-point representation, on the other hand, the number of digits we store for the fractional part can vary. Because of this, and because it is the position of the “point” (.) that determines where the integer part of a number ends and where the fractional part begins, we refer to this representation format as floating-point.

Although there are countless ways to implement floating-point numbers, the one proposed by the IEEE 754 standard in 1985 is the most widely adopted in modern computers. Numbers in the IEEE 754 standard are described by three integers:

- a sign \(s \in \{-1, 1\}\), which determines if the number is negative or positive

- an exponent \(q\), which implicitly sets the boundary between the integer and fractional parts of the number. Informally, we could say that the exponent is what causes the “point” to float

- a significand \(c\) (a.k.a. coefficient or mantissa) representing the actual digits of the number

Given any number \(x\) in base \(b\) (\(b \in \{2, 10\}\) in the IEEE 754 standard), we represent it as a function of the three integers described above:

\[\begin{equation} x = f(s, q, c) \stackrel{\text{def}}{=} (-1)^s \times b^q \times c \tag{1}\label{eq:fp} \end{equation}\]While the role of the sign is straightforward, the roles of the exponent and the significand aren’t obvious. Let’s start by building an intuition about the exponent: previously, we said it’s what causes the “point” to float, or to move left and right. If we take a number \(n\) and move the point very far to the left, we’ll get a very small number compared to \(n\). On the other hand, if we move the point all the way to the right, we’ll get a much bigger number than \(n\). What this tells us is that the exponent is what determines the range of numbers we can represent with our floating-point format. If we allocate a lot of bits to the exponent, and therefore allow its absolute value to grow very big, we’ll be able to move the point very far to the left and to the right. By contrast, if we allocate very few bits to it, effectively preventing it from becoming large, we won’t be able to push the point much far, so the range of numbers we’ll be able to represent will be limited. The technical term for this range is dynamic range.

What about the significand? As we will see better in the upcoming sections, the significand is what determines the granularity of the numbers we can represent with our floating-point format – remember, we can’t represent all real number anyway, as they are an uncountable set. Given a fixed range determined by the maximum value of the exponent, more bits allocated to the significand means that the numbers within that range are more “dense”, i.e. there are more of them. The technical term for this “density” is precision.

Finally, You might wonder if can we also represent special values like \(+\infty\), \(-\infty\) and NaN within this framework. The answer is yes: there are “reserved” values for the exponent that denote precisely these special elements. More on this later.

Common floating-point formats

In this section, I’ll describe how some of the most commonly used floating-point formats are implemented in the IEEE 754 standard.

The IEEE 754 float 32 format

The IEEE 754 float 32 format, often referred to as single-precision, uses 32 bits to represent floating-point numbers. The 32-bit budget is distributed as follows:

- 1 bit for the sign

- 8 bits for the exponent

- 23 bits for the significand

The illustration below shows how the bits are actually laid out in memory:

In addition to the bits you see in the diagram above, every floating-point number actually has one more bit in the significand. This 24th bit, which is also the most significant, is not stored in memory, hence it is not represented in the image. Instead, it is always assumed to be 1 in what is called the normalized representation of a floating-point number (also sometimes referred to as the implicit bit convention or leading bit convention). If it were shown explicitly, it would appear at the far left of the significand (the pink streak in the diagram). Explaining the rationale behind this implicit bit would require a bit of a digression, so I’ll leave it for later.

Now comes the question: how do you go from a sequence of bits like the one above to an actual real number? For instance, which number does the bit sequence above correspond to? For a floating-point number in normalized form, the expression is:

\[x = (-1)^{b_{31}} \times 2^{(\sum_{i=0}^{7}b_{23+i}2^i)-127} \times (1 + \sum_{i=1}^{23}b_{23-i}2^{-i}) \tag{2}\label{eq:binary_to_decimal}\]or if you prefer a more intuitive representation:

Notice a couple of things:

- The exponent is represented in “biased” form, meaning the value stored is offset from the actual one by an exponent bias \(b_e\) (\(b_e = 127\) for float 32). This is done because exponents have to be signed values in order to be able to represent both very small and very large values, but two’s complement, the usual representation for signed values, would make comparisons tricky. By storing the exponent as an unsigned integer, comparisons become straightforward, and the true exponent can be recovered by subtracting the bias

- The “\(1 + ...\)” (or the “1.” in the graphical representation) and the summation index starting from 1 rather than 0 in the rightmost term in the expression jointly account for the implicit bit in the significand. To verify this, let’s call the implicit bit \(b_{imp}\) and add the missing term for \(i=0\) in the summation: this would be \(b_{imp} \cdot 2^i \Rightarrow 1 \cdot 2^0 = 1\)

Here’s a little exercise for you: figure out what number the sequence of bits shown above corresponds to.

Solution (only to check, don't cheat 😉)

Other common floating-point formats

The IEEE 754 standard defines other floating-point formats in addition to float 32. Among these, the most commonly used are float 16 (half precision) and float 64 (double precision). Much less common formats are float 128 (quadruple precision) and float 256 (octuple precision): very few use cases justify the need for such high precision.

But how do all these formats differ from float 32, apart from the number of bits used to represent a number? Well, it’s really just how many of these bits are used for the exponent and the significand! Here’s a compact table that highlights the differences among all the floating-point formats in the IEE 754 standard:

| Format | Sign bits | Exponent bits | Significand bits | Exponent bias (\(b_e\)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| float 16 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| float 32 | 1 | 8 | 23 | 127 |

| float 64 | 1 | 11 | 52 | 1023 |

| float 128 | 1 | 15 | 112 | 16383 |

| float 256 | 1 | 19 | 236 | 262143 |

Normal and subnormal floating-point numbers

As we learned in a previous section, the most significant bit of the significand of a floating-point number is implicitly assumed to be equal to 1 and therefore not stored explicitly. Floating-point numbers that follow this convention are called normal numbers.

What we did not explain, however, is why this bit is implicitly set to 1. Well, it turns out that if we allow it to be 0 too, we would have different but equivalent representations for certain numbers, not to mention we’d have 1 bit less in our budget. This isn’t ideal, as we wouldn’t make an efficient use of our bit budget.

Consider the following example involving the number \(3\): fixing \(b=2\), can we find multiple valid values for \(s\), \(q\) and \(c\) to plug into equation \eqref{eq:fp} to get 3? Check this out:

- \(s=0\), \(q=1\), \(c=1.5 \Rightarrow x = (-1)^0 \times 2^1 \times 1.5 = 3\)

- \(s=0\), \(q=2\), \(c=0.75 \Rightarrow x = (-1)^0 \times 2^2 \times 0.75 = 3\)

- \(s=0\), \(q=3\), \(c=0.375 \Rightarrow x = (-1)^0 \times 2^3 \times 0.375 = 3\)

- …

If you look closely, you might spot a pattern there… did you notice that at each step we’re simply increasing \(q\) by 1 and halving \(c\)? This should make perfect sense to you, as increasing the exponent by 1 means doubling the value of the expression, so we’re just compensating the fact that \(c\) is divided by 2 here. Then, if you read the sequence above in reverse order, you’d realize we could also decrease \(q\) by 1 and double \(c\) to obtain exactly the same result.

But wait, I haven’t shown you the different but equivalent binary representations of the number 3 corresponding to the expressions above! In float 32, for instance, they would look like this (the whitespaces are just a visual aid to separate sign, exponent and significand): ⎡ THE WORLD ⎦

0 10000000 110000000000000000000000 10000001 011000000000000000000000 10000010 00110000000000000000000- …

If you look at the binary representations rather than the high-level expressions, you will spot yet another pattern: the non-zero bits in the significand are progressively shifted to the right as the exponent is incremented by 1. Just to confirm the intuition we built above, think about what those operations mean in mathematical terms: when you shift the bits of the significand to the right, you are incrementing the starting index of the summation in equation \eqref{eq:binary_to_decimal} by 1, which corresponds to dividing the result of the summation by \(b\) (we always have \(b=2\) in our examples). And again, to make up for that and compute the same value for the overall expression, we increase the exponent value (\(q\)) by 1 (cf. equation \eqref{eq:fp}) to achieve the same effect as multiplying the remaining part of the expression by \(b\). Of course, if you were to shift the bits of the significand to the left (e.g. reading the sequence above in reverse order), you’d have to decrease the exponent value by 1.

Now think about what happens if we instead “lock” the first bit of the significand to 1: suddenly, we can’t perform the trick above anymore, therefore we will have a unique representation for each number! Pretty clever, isn’t it? 💡

Sadly, this leads to another issue 😔 Locking the most significant bit of the significand to 1 poses a hard limit on the scale of the numbers we can represent. To see this, let’s try and represent the smallest nonzero number possible (in absolute terms). In order to do that, we would pick \(c = 0\) and \(q = 1\) (\(q = 0\) is a special value reserved for the number zero). Note that the sign doesn’t matter as we’re interested in the absolute value of the number. With this setting, we would get:

\[x = 2^{1-b_e} \times (1 + 0) = 2^{1-b_e} \label{eq:min_normal}\]In other words, we have no way to represent numbers smaller than \(2^{1-b_e}\) due to the “1 +” in the summation in equation \eqref{eq:binary_to_decimal} given by the presence of the implicit bit in the significand. For example, in float 32, the smallest number possible is \(2^{1-b_e} = 2^{1 - 127} = 2^{-126}\). If we were to lay the numbers we can represent with this system in a straight line, we would have a “hole” between \(0\) and \(2^{1-b_e}\).

Enter subnormal numbers: numbers for which the implicit bit convention does not hold, hence do not suffer from the problem described above. But wait a second, we had a very good reason to introduce the implicit bit convention… does that mean now we allow different but equivalent representations to exist for subnormal numbers? No need to worry about that, because another convention applies that comes to our rescue: the exponent value is always \(q_{min} = 1 - b_e\), the minimum possible exponent value. For subnormal numbers, the exponent has a special bit representation: it is all zeros. So when you see all zeros in the exponent’s bit representation, you know you’re looking at a subnormal number (if the bits of the significand are also all zeros, then that number is exactly zero).

So all in all, subnormal numbers allow you to represent numbers that are smaller (in absolute value) than \(2^{1-b_e}\), though with 1 less bit of precision in the significand (no more implicit bit 🙅♂️).

Representation of non-numeric values

In the introduction, I mentioned that the IEEE 754 standard allows one to represent special values like \(+\infty\), \(-\infty\) and NaN in addition to regular floating-point numbers. For this purpose, special bit configurations are reserved. In particular, if the exponent consists exclusively of “1” bits, then you’re dealing with one of those non-numeric values. If the significand consists only of “0” bits, then you’re looking at either \(+\infty\) or \(-\infty\), depending on the value of the sign. If not, you’re looking at NaN.

Exotic floating-point formats 🌴

While float 16, 32 and 64 represent what most people would use in real-life scenarios (also outside of the AI domain), in this section we irreversibly step into the realm of the exotic. The growing need for efficient training and inference of large AI models led researchers to experiment with unorthodox floating-point formats.

The bfloat 16 format

bfloat 16, short for Brain Floating Point, is a 16-bit floating-point format proposed by Google Brain as a tradeoff between the representational power of float 32 and the smaller memory footprint and higher efficiency of float 16. This is simply achieved by allocating the 16 bits budget in the following way: 1 for the sign, 8 for the exponent and 7 for the significand.

But what use cases justify a custom floating point format like bfloat 16? In the context of AI models training, researchers observed that dynamic range (proportional to the number of bits allocated to the exponent), and not precision (proportional to the number of allocated to the significand), is what matters the most when it comes to model convergence. So naturally, when reducing the bits budget from 32 to 16 to save memory and speed up the number crunching involved in training AI models, it makes more sense to “eat” bits from the significand, like bfloat 16 does, than from the exponent, like float 16 does. More on this in the Mixed precision training section.

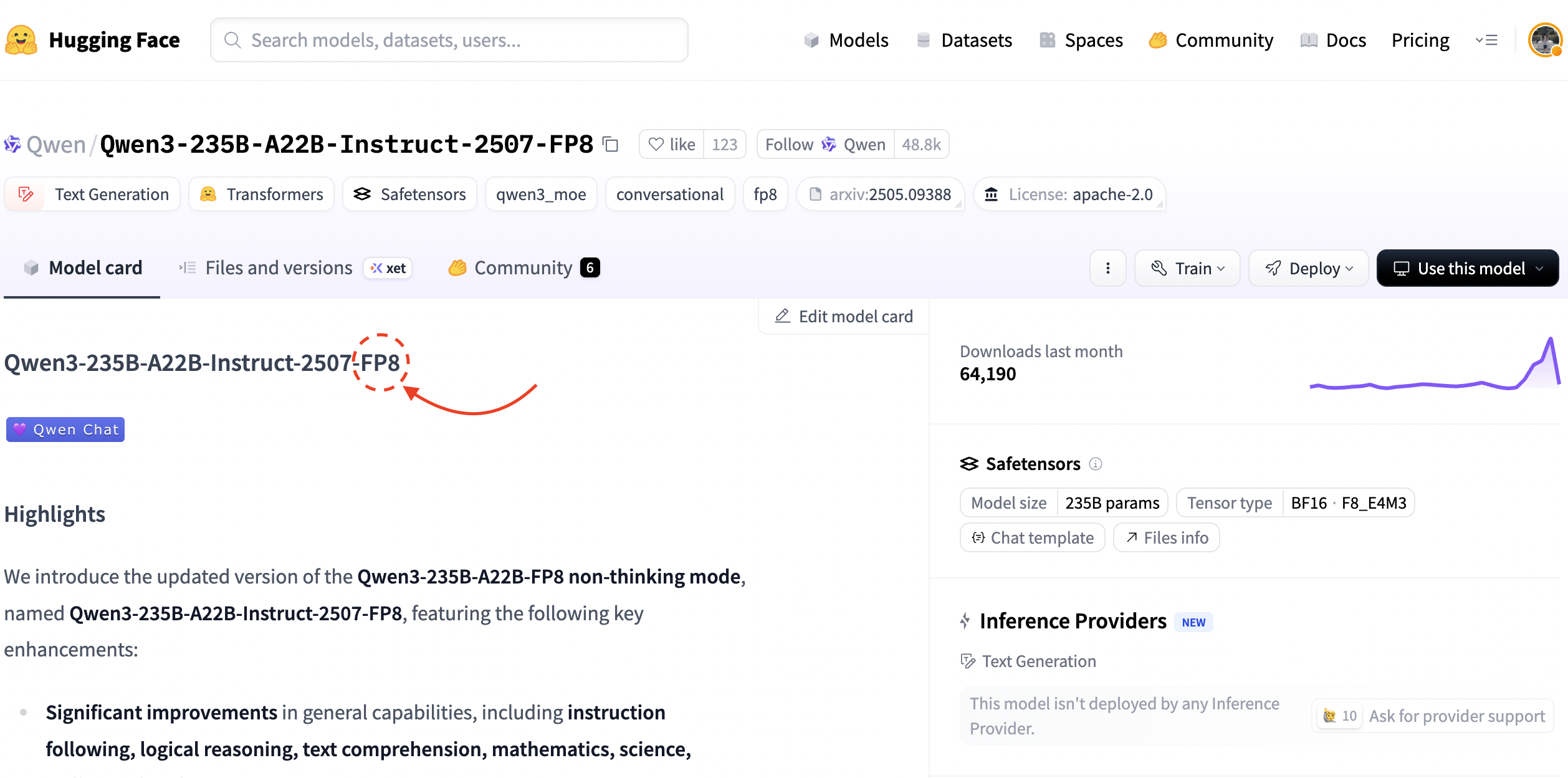

FP8 formats

On the quest for more efficient floating-point formats to use for large-scale AI model trainings, researchers didn’t stop at 16-bit formats and went all the way down to 8 bits. Although it might seem crazy that you can cut out 24 bits virtually scot-free, – remember, we started from float 32 – strong models like DeepSeek-R1 and Qwen3 were trained using precisely this floating-point format (cf. screenshot below).

Two major FP8 formats exist, called E5M2 and E4M3. These awkward names give away their bit allocations: 5 exponent / 2 mantissa (significand) and 4 exponent / 3 mantissa, respectively. Strictly speaking, only E5M2 is IEEE 754 compliant, because E4M3 does not have any special bit configuration to represent \(\pm\infty\).

These formats are natively implemented in the NVIDIA Hopper architecture and can significantly speed up training and inference of large AI models. From a software perspective, they are implemented in PyTorch since version 2.2.0:

torch.float8_e4m3fn

torch.float8_e4m3fnuz

torch.float8_e5m2

torch.float8_e5m2fnuz

The “fn” suffix stands for “finite only”, meaning that \(\pm\infty\) is not representable and replaced by NaN. The “uz” suffix stands for “unsigned zero”, meaning that \(-0\) doesn’t exist and is replaced by \(+0\).

Please note that, in PyTorch, these are storage types and not compute types, meaning that mathematical operations are not defined over them. If you want to use float 8 as a compute type, you need to use other specialized frameworks like TorchAO.

TensorFloat 32

TensorFloat 32 is a floating-point format designed by NVIDIA to optimize computations on Tensor Cores, which are AI accelerators supported by the NVIDIA Volta GPU architecture and later ones (Ampere, Hopper, Blackwell). This floating-point format is a bit of an outlier in that its 19-bit budget is not a power of two, unlike other formats. The 19 bits are allocated as: 1 for the sign, 8 for the exponent and 10 for the significand. Because of this, we can regard TensorFloat 32 as a middle ground between float 32 (same dynamic range) and float 16 (same precision).

Another oddity related to this floating-point format is that in terms of storage, it is exactly like a float 32, so it occupies 32 bits. However, by dropping some bits from the significand, computations involving these numbers become much faster in Tensor Cores. As a concrete example, TensorFloat 32 running on Tensor Cores in A100 GPUs can provide up to 10x speedups compared to float 32 on Volta GPUs.

Not only can TensorFloat 32 speed up computations compared to float 32, but it can also retain high accuracy for most use cases, so much so that it is the default computation format in cuDNN (NVIDIA’s highly-optimized Neural Network library) on Ampere hardware and later. So whenever you’re doing, say, a matrix multiplication or a convolution using cuDNN in float 32 on a A100 GPU, you’re actually using TensorFloat 32 under the hood.

Representation capabilities of different floating-point formats

If there’s anything we’ve learned so far, it’s that floating-point formats only differ in how the bit budget is allocated among sign, exponent and significand. In the introduction, we explained how the bits allocated to the exponent are directly related to the dynamic range of that floating-point format, whereas its precision is determined by how many bits we leave for the significand. With the help of a little hands-on experiment, let’s see what are the representation capabilities (combination of dynamic range and precision) of different floating-point formats.

🙌 Hands-on: representation capabilities of floating-point formats (requires Python and PyTorch)

Step 1: Download the helper file fp_formats.py

wget https://gist.githubusercontent.com/anferico/70ab7bc6ec13f4992de17cfeb2897888/raw/f41bbf4ecae433fea5e9c2416ccef6ca44079ccc/fp_formats.py -O fp_formats.py

Step 2: Import the FloatingPointFormat class

from fp_formats import FloatingPointFormat

Step 3: Define a floating point format, for example bfloat 16:

bfloat16 = FloatingPointFormat(n_exponent_bits=8, n_significand_bits=7, symbolic_name="bfloat16")

Step 4: Check the precision of bfloat 16

one = bfloat16.normal_from_binary("0 01111111 0000000")

ones_successor = bfloat16.normal_from_binary("0 01111111 0000001")

print(one)

print(ones_successor)

In this code snippet, we are defining the number \(1\) in bfloat 16 via its binary representation: the sign bit is 0, so it’s a positive number; the biased exponent is \(2^7 - 1 = 127\), so the actual exponent is \(127 - 127 = 0\); the significand is 0. So, putting everything together, we get \((-1)^0 \times 2^0 \times (1 + 0) = 1\). Then, to get the number that follows immediately 1, we flip the least significant bit of the significand to 1. Run the code snippet above to see what you get, or click on “Show output” below.

Show output

1.0 1.0078125

Think about the implications of this: if the successor of the number 1 is 1.0078125, it means there’s a “hole” between them 😨 Also, the “diameter” of this hole is shockingly large: almost \(\frac{8}{1000}\). But what happens if we try to represent a number that lies within this hole using bfloat 16? 🤯

Step 5: Peek inside the hole

For this example, our lightweight library won’t be enough as it doesn’t implement the bfloat 16 floating-point format in its entirety with truncations, mathematical operations and so on, but it only provides a way to represent it inside a more expressive floating point format, i.e. float 64 (Python’s default). Instead, we’ll use PyTorch as it contains a full implementation of bfloat 16:

import torch

print(torch.tensor(1.0, dtype=torch.bfloat16))

print(torch.tensor(1.001, dtype=torch.bfloat16))

print(torch.tensor(1.005, dtype=torch.bfloat16))

print(torch.tensor(1.0078125, dtype=torch.bfloat16))

Show output

tensor(1., dtype=torch.bfloat16) tensor(1., dtype=torch.bfloat16) tensor(1.00781250, dtype=torch.bfloat16) tensor(1.00781250, dtype=torch.bfloat16)

Interestingly, if you attempt to represent an unrepresentable number in a given floating-point format, it gets approximated with the nearest representable number in that format. As an exercise, you could repeat the same experiment with float 16 and see what changes.

What the experiment above taught us is that relatively large “holes” exist between consecutive floating-point numbers. Now what if I told you it can get a lot worse than that? As it turns out, the diameter of these holes is proportional to the exponent value, meaning that large numbers are more “spread out” than small numbers. Check the figure below to get a sense of this, again taking bfloat 16 as an example:

As you can see, the numbers from \(0.5\) to \(1\) are about \(0.0039\) units away from each other. However, numbers from \(1\) to \(2\) are twice as distant, i.e. \(0.0078\) units. And unsurprisingly, numbers from \(2\) to \(4\) are \(0.156\) units apart. The one to blame for this weird behavior is the exponent: whenever we take a small “step” in the number line by increasing the significand by \(\delta_c\), the exponent amplifies that step and makes it \(b^q\times \delta_c\) (cf. \eqref{eq:fp}), so larger values of \(q\) make the amplifying effect worse. On the contrary, the problem isn’t as bad in the neighborhood of \(0\) as the exponent gets progressively smaller as we approach it.

Mixed precision training

Since my main interests and experience revolve around the world of AI, I thought I would include a section about a very relevant application of unconventional floating-point formats in the field of AI, namely mixed precision training. As the name evokes, mixed precision training is about using two or more floating-point formats while training an AI model. The reason this makes sense is because using 16 or 8 bits to represent weights, activations and so on as opposed to 32 results in a much lower memory footprint and increased efficiency owing to specialized hardware (for example, NVIDIA Hopper GPUs supporting float 8 computations natively). But if using fewer bits has such nice upsides, why bother “mixing” different precisions, i.e. floating-point formats? Can’t we just stick with e.g. bfloat 16 or float 8?

Well you probably know the answer, right? If you followed the previous sections carefully, you’d know that using fewer bits comes with a cost, that is decreased precision and/or dynamic range. Mixing different floating-point formats within the same training run helps tackle such issues. In some cases, like when using bfloat 16, this is good enough; however, when using formats like float 16 or float 8 that feature limited dynamic ranges, we actually need additional tricks to make it work. Let me elaborate a little bit on my previous two statements.

By default, mixed precision training takes advantage of specialized hardware (e.g. NVIDIA GPUs) and software (e.g. cuBLAS and cuDNN) to run computations like matrix multiplications and convolutions in a low-precision floating-point formats with accumulations in a higher-precision format like float 32 to retain as much accuracy as possible (note: “accumulating” refers to storing intermediate results before computing the final ones. For instance, when computing a dot product between a vector \(v\) and a vector \(w\), you need to accumulate each \(v_i \times w_j\) to compute the final result). So when you’re running a bfloat 16 training using, say, PyTorch, you’re actually “mixing” bfloat 16 and float 32 (for accumulations).

When you have a limited dynamic range, however, you might face a more severe issue: underflows or overflows. When training neural networks, in order to compute the gradients of each parameter with respect to the loss value, you need to use the back-propagation algorithm to properly combine the “contribution” of each parameter to that particular loss value. Combining such contributions literally amounts to multiplying individual gradients together, and that’s where the problem arises. Multiplying several numbers together can lead to very small, if the numbers are \(<1\), or very big, if the numbers are \(>1\), results. And if the results get so small or big that they cross the boundaries of your floating-point format’s dynamic range, that’s where the trouble begins, because you start having NaN gradients, which lead to NaN parameters, which lead to NaN loss, which leads to your training being entirely compromised.

So the clever trick that mixed precision training applies is to scale the loss value to bring gradients back withing the boundaries of the floating-point format’s dynamic range. This trick leverages a simple fact, that is the linearity of differentiation:

\[\nabla_\theta (\lambda \cdot L) = \lambda \cdot \nabla_\theta L\]where \(\theta\) are the model parameters, \(L\) is the loss value and \(\lambda\) is the scaling factor. So in other words, scaling your loss value by \(\lambda\) scales your gradients by the same factor.

Wrapping up

In this post, we explored the world of “exotic” floating-point formats, focusing on their structure, trade-offs, and practical implications for training large-scale neural networks. We compared standard formats like float 32 with alternatives such as bfloat 16, highlighting how changes in bit allocation affect precision and dynamic range. Through hands-on experiments and visualizations, we saw how these formats impact numerical accuracy and efficiency, especially in the context of mixed precision training. Ultimately, understanding these formats gives AI practitioners the right tools to make informed choices for training and inference workloads, balancing performance and memory footprint.

-

Strictly speaking, since you can store only a finite amount of digits for a given number in a computer, there is no way to represent the full set of real numbers \(\mathbb{R}\) (for instance, irrational numbers like \(\pi\) or \(e\) cannot be represented). Indeed, we can only represent (a subset of) the rational numbers \(\mathbb{Q}\). ↩